ELLSWORTH KELLY'S LAST WORK WAS A CHURCH –BUT NOT (HE WAS AN ATHEIST)

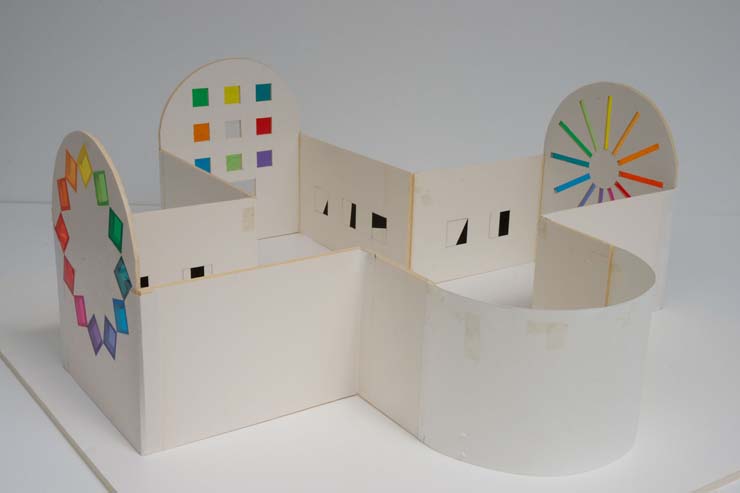

Ellsworth Kelly was one of the most celebrated artists of the 20th century. His minimalist paintings and sculpture are in the collections of museums around the world. Kelly died in 2015, at the age of 92, and continued to work right up until the end from his home in upstate New York, in Spencertown. But his final work was just unveiled in Texas, one he never saw completed. It is the most ambitious work the artist ever made: a 2,700-square-foot building loosely modeled after a Romanesque church.

Austin was the name of the monumental last work and is also the name of the city where it stands in Texas. It’s a freestanding stone building with colored glass windows that is now part of the Blanton Museum’s permanent collection.

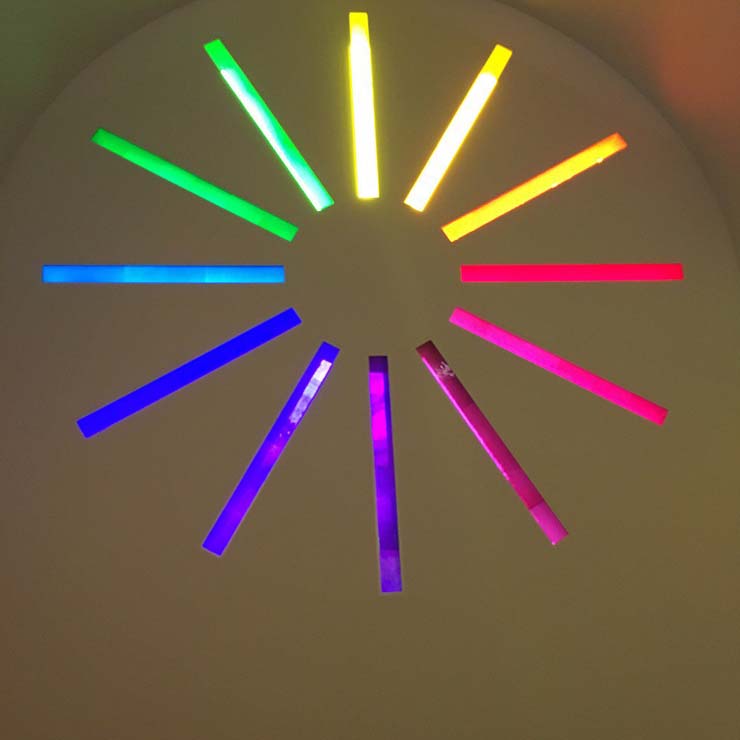

For the past two years, the construction of Kelly’s last work has been the object of much curiosity. As the stone curves of the structure began to take shape, students snapped pics posted on Instagram by the scores. The front contains a nine-square grid of colorful blown glass windows, while a circle of tumbling squares adorns one side and a starburst pattern the other.

The Blanton has been developing the project since 2012, but it has actually been in the works for decades. Kelly originally intended to build the structure on the California vineyard of the late TV producer Douglas Cramer, who collected Kelly’s work and offered to commission it in the 1980s. But the artist ultimately decided the project was too important to him to place on private land, which could be sold. According to Blanton curator Carter Foster,

“It eventually did get sold.”

The museum raised $23 million for the project, which includes a $4 million endowment to conserve the work. Blanton director Simone Wicha said,

“This is a game changer for this city and for Ellsworth Kelly, to have his most monumental work realized.”

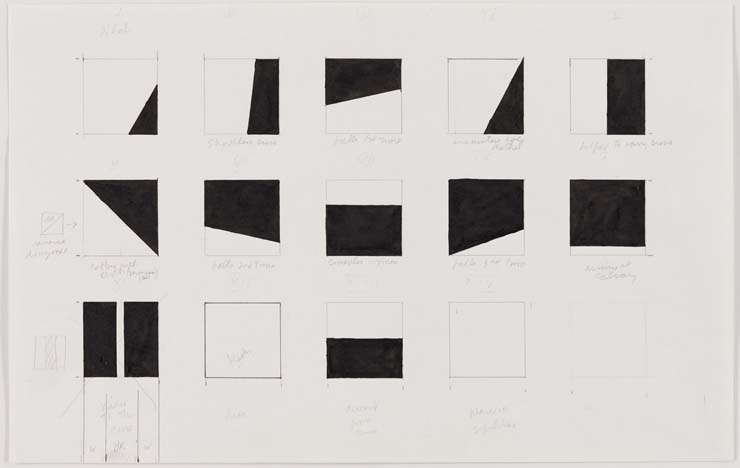

Ellsworth Kelly, Eglise, Marly, 1944, ink on paper

8 ¼ x 5 ¼ inches, Blanton Museum

Kelly first became fascinated by the architecture of Romanesque and Cistercian cathedrals while stationed Paris during World War II. Foster said, the building’s two double-barrel vaults, give the viewer,

“A processional aspect to the way you’re experiencing it… like if you go into a chapel or church in Europe it’s usually filled with side chapels but you’re directed to an altar with a cross at the end, and you meander around the sides.”

During the nearly seven years he remained in France, he sketched the cathedrals at Chartres and Notre Dame, showing particular interest in the interstitial spaces and the geometries of the stonework and monstrances. A number of these early drawings are included in the exhibition, Form Into Spirit, now on view at the Blanton through April 29.

Kelly & Jack Shear. Photo, Patrick McMullen

Kelly was gay, which is not something any of the articles on this new work I read even discuss or really ever even mention unless, Jack Shear comes up. He is always referred to as his “longtime partner” and he is now the head of his foundation. Kelly worked with colors of the prism. (Yes, the RAINBOW.) When he set out to create his own version of a chapel, he left out religious imagery and chose not to have it consecrated. It’s a chapel-like form stripped of any holy narrative.

Even though Kelly’s work is about form and color, I’ve never heard it mentioned by Kelly, but the rainbow, which is certainly not the sole ownership of LGBTQ people, still represents us (and Kelly, even though he might not have subscribed to it) and you can’t help but see it here, even in pictures. In person it must be MUCH more powerful and prevalent. Straight people sometimes complain that gay people layer “being gay” onto everything but it’s not lost on me that this gay artist, an avowed atheist, created a church that features rainbow stained-glass. “Hand-blown”, no less! (The colored glass was apparently created by Kelly layering 4 colors and having the colored panels created by blown glass.)

Austin is both a sanctuary for the visitor and a temple to the near century-long devotion to color and form that was Kelly’s oeuvre. Shear pointed out during a panel discussion at the museum after the building opened that there is an element of Kelly’s studio in the building,

“The studio as a place of solitude.”

Religious or not, it seems fitting that the last work is a place of reflection and solitude, two of this artist’s stock and trade, are the intended and lasting final effect.