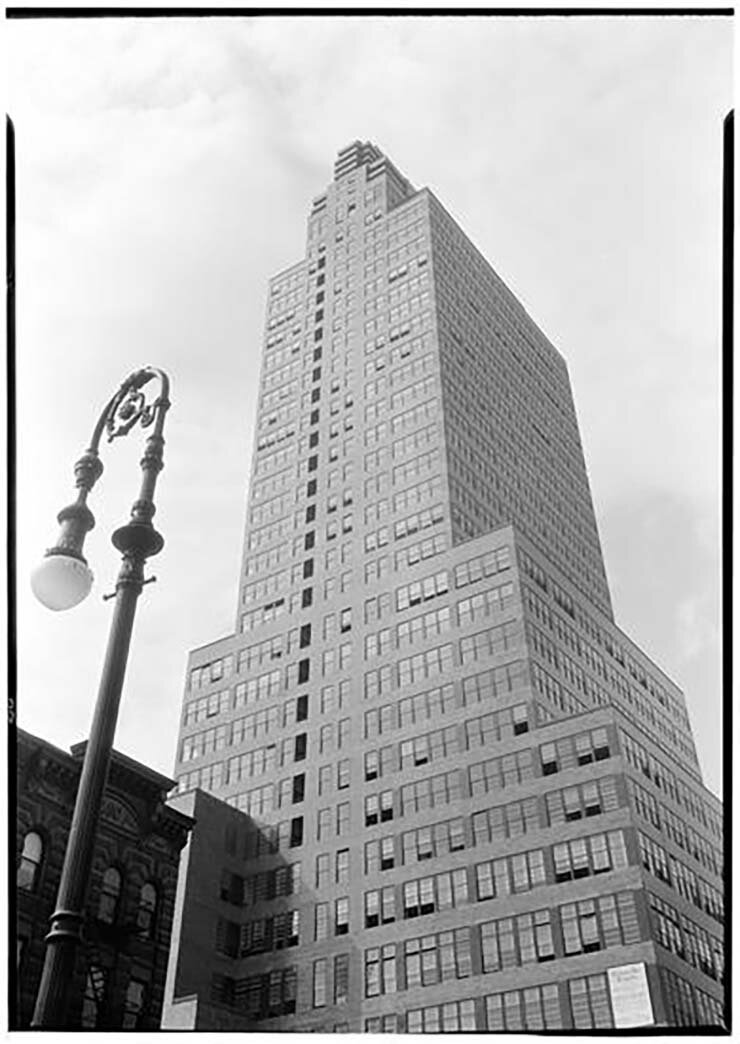

THIS LANDMARKED DECO MASTERPIECE WAS JUST DESTROYED OVERNIGHT...

Completed in 1931, the McGraw-Hill Building has been a city landmark since 1979.

According to the designation report on file at the LPC, the Raymond Hood, Godley & Fouilhoux design

“was the product of the gradual shift in architectural taste from the machine-age abstract decorativeness of the Moderne or Art Deco style to the corporate-age utility of the International Style, and of the constantly innovative and growing architectural genius of Raymond Hood.”

Last week the exuberant Art Deco lobby at midtown iconic McGraw-Hill Building was demolished. Deco Tower Associates (which owns the 35-story tower) conducted a $40 million exterior restoration, the company demolished the lobby in spite of swiftly organized protest.

Speaking with neighborhood publication W42ST last Thursday, New York state senator Brad Hoylman said that the lobby

“was demolished, apparently under the cover of darkness, with no public notice.”

David Netto told Architectural Digest,

“There’s no question the McGraw-Hill lobby was one of the strongest pieces of Art Deco design left in the city.

Besides the intrinsic value of Raymond Hood’s interior for its drama and chromatic boldness, this lobby in particular had a seamless relationship with the exterior of the building, now mutilated

The short-sightedness of landmarking one and not both is a recent example of the kind of ignorance of heritage and toadying to developers that the 1970s was full of, and which I had thought we [had gotten past].”

Thomas Kligerman, partner of Ike Kligerman Barkley, notes that the unity between interior and exterior was not academic. Rather, it was legible to any observer:

“Raymond Hood’s McGraw-Hill Building was new when my grandfather was a young man, and he talked about it with the pride of an owner. In particular, he loved the bronze, stainless-steel, and green-painted bands that swept you from street to lobby in a nearly audible whoosh.

I can only hope that the news of this demolition will spur those of us interested in New York’s design history—as well as those ignorant of it—to put an end to such destruction.”

According to AD PRO,

Deco Tower Associates had tested the limits of landmark protection earlier this year, when on January 13 it had proposed removing the 11-foot-tall terra-cotta “McGraw-Hill” signage that crowns the building as part of an otherwise sensitive exterior alteration package aimed at a new generation of office occupants. Earlier that same month, the owner had already received a permit to demolish the lobby, but word of the demolition did not get out until just prior to a February 9 LPC hearing that was formally scheduled for discussion of the exterior alterations.

When concerns about the lobby came up during the hearing’s public comment period, according to journalist Christopher Bonanos,

“The commissioners seemed taken aback at the excitement about a topic that wasn’t on the agenda and over which they had no jurisdiction. Several members seemed a little surprised to hear that the lobby was at risk and indicated they would be in favor of protecting it.”

As for the subject officially under discussion? New crown signage was removed from that package, designed by New York–based MdeAS Architects. LPC unanimously approved the changes.

In the wake of the February 9 hearing, scholars and activists engaged in a rapid, highly coordinated effort to have the LPC evaluate the McGraw-Hill lobby for landmark protection. Kriskiewicz comments that, had there been more lead time, these champions would have easily sparked a groundswell of public support, but demolition took place prior to an emergency evaluation.

Deco Tower Associates told The Architect’s Newspaper that elements of Hood’s original lobby have been salvaged and catalogued, and that they might be incorporated into the new design.

Architect Richard Southwick, a partner at Beyer Blinder Belle who directs the global firm’s historic preservation efforts says,

“The demolition of the McGraw-Hill lobby is an unfortunate and irreversible act that cannot be mitigated by the reuse of salvaged remnants placed out of context into a contemporary design.

Modern requirements could have been layered onto the historic space, [but b]etter now to provide an exhibit as a reminder to what is gone forever than to cannibalize the relics of the lost lobby.”

Architect Belmont Freeman agrees saying,

“The developer and architect may claim that they will incorporate elements of the original lobby in the new design, but that is no consolation and, in fact, compounds the insult.

This should be a lesson to the LPC, when designating architecturally significant commercial buildings, to consider the lobby an essential part of the package.”

In the meantime, Ryall Sheridan Architects cofounder William Ryall says that the LPC’s current commissioners should resign,

“In our current American world of unfettered capitalism, money ultimately and efficiently makes decisions, giving everyone an excuse and alibi for their irresponsible behavior.”

(via AD)